"Home Going Service Ms. Vickie Lynn Obey" Feb 28, 2026 11AM Live Stream

"FBCWest Music Extravaganza" 11/23/2025 4PM Live Stream

"Moral Monday" Bishop William Barber, Live Stream 7PM 10/24/2025

Sister Jessie Lee Franks Irby, Homegoing Service - Saturday May 31, 2025 12Noon

Home Going Service Mrs. Jessie Lee Irby

12PM May 31, 2025

Sister Learlena Thompson (Sister of Deacon Marian Yates) Homegoing Service

Home Going Service Sister Learlena Thompson Saturday February 15, 2025 12Noon

Sister Mildred S. Grier Homegoing Service

Mrs. Mildred Grier Funeral Service - Saturday March 16, 2024 11:00AM

"Just Action" Richard Rothstein - Leah Rothstein - 06/12/2023 Live 6:30PM

Deacon William C. Spivey Jr. Homegoing Service

Walter Patterson Homegoing Service; Brother-In-Law of Sister of Candice Cochran

Gwendolyn Robinson Atkinson Homegoing Service; Sister of Deacon Genevieve Brown

Sister Minnie Wilson Homegoing Service

Brother Reginald Wilson Service

NEWEST AKA

Congratulations to Ryann Asbury (Winston-Salem State University) on becoming

one of the newest members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.

SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS

Charlotte Post Top Senior

|

|

Congratulations to Erin Spivey Daughter of William & Ericka Spivey for 2021 |

New DST Sorors

Congratulations to Kaycee Hailey (Duke University) and Genevieve “Genni” Ellis (North Carolina Central University) on becoming the newest members of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

|

GAME ON! JOSH GROSS

SALUTE TO

BROTHER JOSH GROSS

THE NEW HEAD MEN'S BASKETBALL COACH

AT JOHNSON & WALES UNIVERSITY

MARCH MADNESS

| Congratulations Brother Brandon Lewis, Director of Basketball Operations/Assistant Coach at Belmont Abbey College, cutting down the net at the southeast regional championship. The women's team went to the Division II Elite Eight tournament. |  |

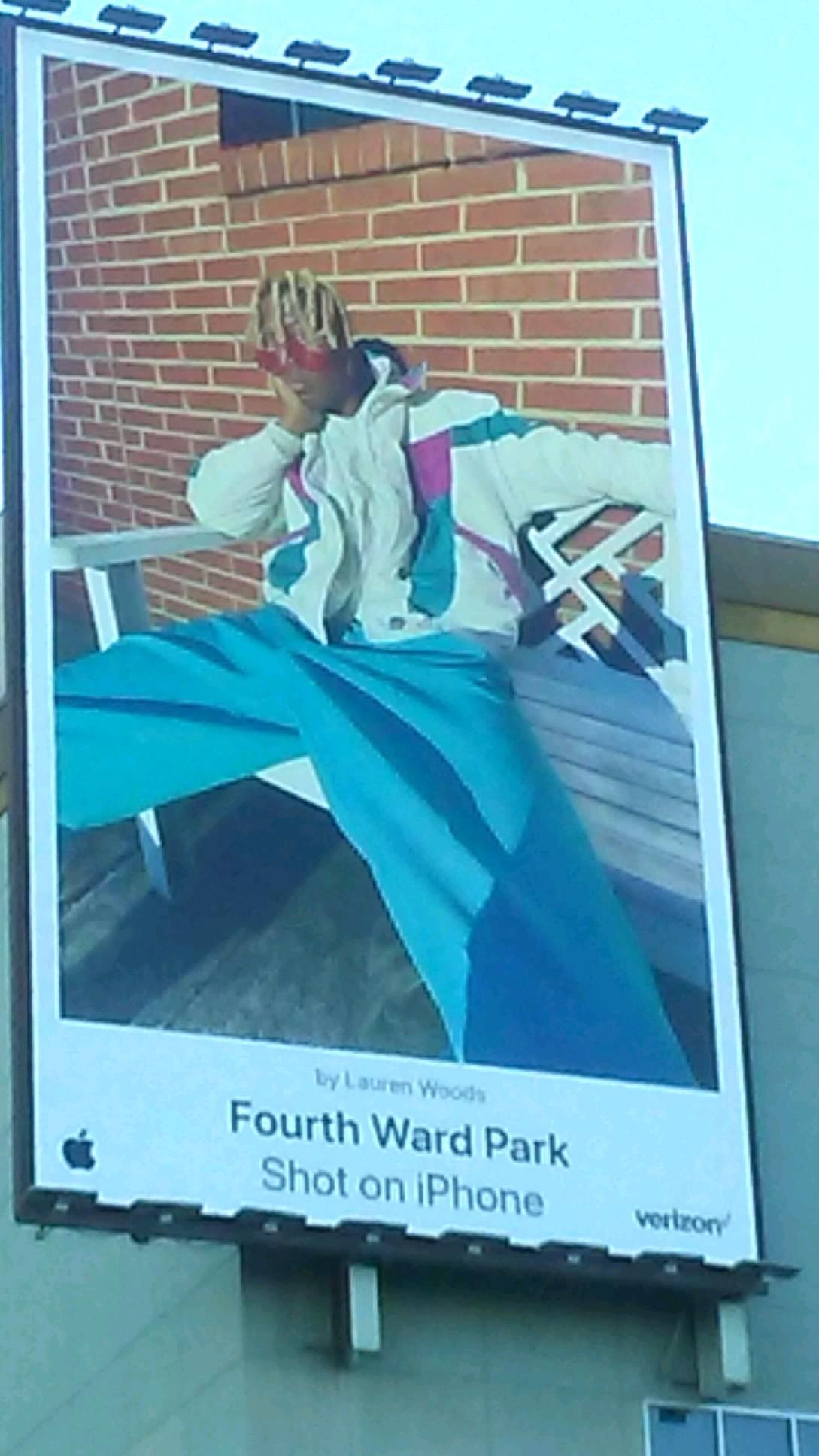

APPLE BILLBOARD PHOTOS

|

|

SALUTE TO SELECTED BY APPLE

(Look for Another Billboard Coming Soon on I-277)

|

50 YEARS OF CHARMS

|

|

The Charlotte Chapter of Charms, Inc. Sister Maxine Davis & Sister Christine Bowser |

Rev. John Burton on Style List

| Rev. John Burton, FBC-W's youth minister, was named to SouthPark Magazine's IT List -- 26 of Charlotte's Most Stylish Men and Women. The magazine's 2020 IT List focused entirely on some of the most stylish Black men and women in Charlotte. For more info, click here for SouthPark Magazine. |

|

2nd Birthday for Sister McClain

reprinted from Qcitymetro.com

By Adriana Burkins – March 16, 2015

This article is part of a series spotlighting local people who have made a decision to get healthier by enrolling in Village HeartBEAT, a 16-week wellness program designed to reduce risk factors, especially in the African American and Latino communities. The program, now in its third year, is sponsored by the Mecklenburg County Health Department and works primarily with local churches.

After three years on dialysis, Henrietta McClain says she is now doing fine, thanks to a donor kidney. The experience has focused her attention on health. (Photo: Glenn H. Burkins, Qcitymetro.com) |

Name: Henrietta McClain

Church: First Baptist Church-West

Risk factors: Kidney failure due to high-blood pressure

Her Story: Almost every weekday, Henrietta McClain can be found somewhere getting in her exercise, often at the Johnson C. Smith University HealthPlex, where fitness instructors know her by name.

McClain has a good reason for her focus on health. In August 2006, she underwent a kidney transplant – an event she now marks as her second birthday.

McClain said she developed high-blood pressure in her 20s, which led to kidney failure. The transplant, she says, was like a miracle.

She had been on dialysis for three years. Instead of receiving dialysis in a medical center, McClain chose to go through the treatments in her home. This required inserting a tube into her abdomen every night to flush out the toxins in her blood. She said her children, her church and her job kept her going through those difficult years.

This year marks her second year as a Village HeartBEAT participant. McClain says her blood pressure is now at a normal level and her kidneys work “great.” To stay fit, she follows a fitness regimen that includes cardio exercises, circuit training, line dancing and healthy eating.

Her advice: “Take medication. I think that’s very important because I have to take mine for the rest of my life to prevent my body from rejecting the kidney. People are surprised about the number and quantity of drugs that an organ transplant patient must take everyday. And keep active. If you can get in any programs that can help you…keep active, do that.”

Importance of donors: “Organ donors can give the gift of love and life. Someone donated a kidney to me, so I feel really strong on that. I’m an organ donor, and I advise my children to do so. You don’t realize the importance of it until you get sick.”

GOLD STAR MEMBERS

MILESTONES

- A coporate donor provided more than 150 coats to needy families in the name of First Baptist Church-West.

- First Baptist-West is sponsoring the full tuition of two Liberia students through the Lott Carey Foreign Missions Program.

First Baptist-West Son Moves On

With so many local connections, many in the FBC-W Family wanted to keep him close. But,

Aaron also says he couldn’t have found a better mentor or friend in

By moving to

Rev.

He hopes to do the same in

The FBC-W son graduated from North Mecklenburg High in 1987. He received his B.A. degree in Dramatic Literature from

He is married to

FBC-W MEMBER MAUDE BALLOU & MLK, JR.

By Karen Heller, The Washington Post

RIDGELAND, Miss. — In this comfortable suburb north of Jackson, Maude Ballou sits among other residents, chatting about lunch, the weather and the daily pleasures of life in a congenial retirement home. She spends her days quietly, reading — the Bible, mostly — and catching up with family and friends.

It wasn’t always so.

In the 1950s, Ballou lived in Montgomery during a turbulent, violent time in Alabama’s capital. She worked there for a nascent civil rights organization, the Montgomery Improvement Association, doing almost daily battle with fierce opponents, including the segregationist White Citizens’ Council and an intransigent political culture hellbent on keeping the city as it had been when it was the first capital of the Confederacy — and keeping blacks firmly in their place.

Ballou, now 89, was there as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s first personal secretary.

“Though I was much more than that,” says Ballou, her elegant tapered fingers resting on her freckled cheek. “I booked flights, research, writing. I did it all.” This included editing versions of the “I Have a Dream” speech that King delivered at Southern churches long before the 1963 March on Washington.

The release of the movie “Selma,” commemorating the 50th anniversary of the civil rights march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery, and the widespread recent protests that followed racially charged incidents involving the police and African Americans, have sparked renewed interest in the tumultuous years of the civil rights movement and its iconic leader. And few people were closer to King in those early years than Maude Ballou.

An intense loyalty

Maude and Martin — she always called him Martin, although her husband and other people knew him as Mike — were dear friends before her stint working with him in Montgomery from 1955 to 1960. It was the time of the seismic bus boycott of 1955-1956 that put the civil rights movement on the map. King, still in his 20s and completing his doctoral dissertation, went from being a Southern preacher to a civil rights leader of international renown. The basement office of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church was flooded with correspondence and speaking requests. In “Stride Toward Freedom,” King’s 1958 account of the Montgomery boycott, he thanks Ballou, who “continually encouraged me to persevere in this work.”

Ballou, the middle-class daughter of an educated minister, had attended college at Southern University in Baton Rouge, where she studied business (including stenography) as well as American and Western literature. So she had the skills that King required in an assistant.

She had also worked in a factory during the war and later as program director at WRMA, Montgomery’s first black radio station, and had a strict work ethic. King “asked me to work for him on several occasions,” she says. “I did not agree until three or four times.”

Martin and Coretta King and Maude and Leonard Ballou socialized regularly, visiting one another’s homes for what Maude calls “little parties.” Leonard, a talented organist and pianist, taught music at Alabama State and helped Coretta, who had studied voice, with her singing. Maude and Martin had similar backgrounds.

“Our fathers were Baptist ministers,” Ballou says — Martin Luther King Sr. was a giant in Atlanta; H.P. Williams was a presence in Mobile. “We were close. We just bonded, I guess.”

Now using a wheelchair, this self-professed “Southern belle” with the manners to match has lived through plenty, though she is reluctant to share all that she knows. The mother of four, grandmother of 11 and great-grandmother of one declines almost all interview requests. Private and reserved, Ballou is intensely loyal. Like most assistants to celebrated men, she learned to keep secrets and not tell stories out of school.

Ballou was nonetheless in the spotlight in 2011, when the King estate sued her son Howard, a Jackson television anchorman, to take possession of documents that members of his family claimed rightfully belonged to them. Two years later, the court ruled in Howard Ballou’s favor. The Ballous subsequently auctioned 100 pieces of personal memorabilia, including daily calendars, a letter opener and King letters to Ballou from his 1959 five-week sojourn in India (“The Land of Gandhi,” as he put it). The family netted $104,000, most of it going to pay legal bills, although a portion was allocated for a scholarship fund at Alabama State.

But the Ballou family kept plenty of souvenirs from that time, including a letter from Rosa Parks, who famously helped launch the bus boycott; steno pads filled with Ballou’s exquisite hand; datebooks in which she sporadically recorded the day’s events.

From Maude’s personal diary: March 13, 1956 So much work we often come back at night. This was the week of the trial [on the bus boycott]. Seemed as though mail would never stop coming nor telegrams and long distance calls for Rev. King, Jr. This really is a hectic week. We made it though. Very few letters are of adverse nature.

Another entry reads:

March 16, 1957: I saw an old white woman with a pail soliciting contributions for the maintenance of segregation. She asked one man who passed and he smiled warmly saying he had already contributed. I passed this woman several times intentionally to see the class of people who gave – I saw nobody give. The man she asked was a little better off than she, which wasn’t saying much.

Maude Ballou and King, shown here in the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church office, worked together during the early years of the civil rights movement, a turbulent time that included the Montgomery bus boycott, which led to the desegregation of public buses in the South. (Ballou family archives)

March 19,1956: King, center, appears at noon recess on the first day of trials in the Montgomery racial bus boycott. (Gene Herrick/Associated Press)

Daredevil days

Violence soon shattered Montgomery. Historian J. Mills Thornton describes the period as “a reign of terror” and “the dark night of the soul for the movement.” In January 1957, Ralph and Juanita Abernathy’s house, down the street and around the corner from the Ballou home on Tuttle Street, was bombed. The Cold War was in full throttle, and “my older sister asked our mother if the Russians were coming,” her son Leonard recalls. “She explained to us that some bad people had bombed Reverend Abernathy’s home, but that the Abernathy family was all right.”

Four days later, Montgomery Improvement Association leaders supplied the chief of the highway patrol with a “List of persons and churches most vulnerable to violent attacks.” King registered at the top. Mrs. Maude Ballou was No. 21.

“Maybe I didn’t have the sense to worry,” says Ballou, who later spent three decades as a college administrator and a middle and high school teacher in North Carolina. “I didn’t have time to worry about what might happen, or what had happened, or what would happen,” she says in the cadences of a Baptist minister. “We were very busy doing things, knowing that anything could happen, and we just kept going.”

One time a man came down from Birmingham. “He said the White Citizens’ Council had sent him down there to tell me to stop working for civil rights or they would get my children. And that’s what got me, when you think about your babies. That really shook me,” says Ballou, with considerable equanimity. “But it didn’t stop me.”

Another night, working late in the office, alone, “somebody was outside watching. They were outside there in the car. And I found out later it was the KKK. But I was not afraid, for some reason,” she says. “I was a daredevil, I guess.”

Those days were heady, but often wretched. The victorious bus boycott was followed by internecine squabbles within the association. May 1, 1957 11:00 Executive Board meeting. Explosive.

After the association stalled, and King returned to his hometown of Atlanta to helm the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Ballou continued to work with him in the Georgia capital for a year and a half, even living with the Kings for a while.

Taking a stand

Ballou did not travel with King, nor march with him later in Washington and Selma. That was not her role.

“I didn’t have time for that,” she says. “I had work and family.”

She was paid for her work; not much, but enough to cover the cost of a caregiver for her children. Her duty was at a desk, her contributions meted out in correspondence and flight reservations.

Historian David Garrow, author of the monumental King chronicle “Bearing the Cross,” says that “Maude was dealing with both King’s travel schedule and this huge amount of incoming mail” in the years after he landed on the cover of Time magazine and was perpetually overextended. “You look through the papers of the Montgomery period, and up to 85 percent of the signatures are in Maude’s hand. There’s no question that she’s running his life, that she’s the number one person he’s relying on to get the work done.” She handled correspondence from Malcom X, Thurgood Marshall, Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte.

Ballou was not part of the bus boycott, either, though she did make a stand. She is light-skinned, enough to pass as white had she chosen, a choice that never seemed to occur to her. The Southern belle dressed exquisitely. “I wore high heels. I thought I was a fashion model.” Photos from the period, showing a lovely, perfectly coiffed woman, confirm that she was right to think that.

“I got on the bus. The bus was empty, and I sat down,” she says, referring to the front section, reserved for whites. “And the man said, ‘Come here. Is you white?’ And I looked at him, and I said, ‘What do you think?’ And he said, ‘Get back there!’ ”

Mrs. Maude Ballou of Tuttle Street would do no such thing.

“And I got off the bus and walked up the hill to my house,” she says.

King’s handwritten inscription to Maude Ballou in a copy of his 1958 book, “Stride Toward Freedom.” (Ballou family archives)

A flier from the Ballou family collection of King-related documents. The family prevailed in a suit by the civil rights leader’s estate for possession of some of the documents. (Ballou family archives)

Remembering silently

The threats on King’s life increased with his fame. Ballou, a woman of considerable reserve, claims not to have worried about King, even after he was stabbed in Harlem in 1958, and she helped take care of the work that continued to pile up in the aftermath.

“I just had a strong belief he would overcome all this,” she says. “One evening, Martin called and said, ‘Tell Leonard not to bring you to work. I’m going to pick you up, Maude.’ He told me, ‘I dreamed last night that I died and nobody came to my funeral.’ And I told him, ‘Oh, Martin, no, no. That is not going to happen.’ He was serious. That got to me.”

In April 1968, when King was assassinated, it was the rare time that Howard Ballou recalls seeing his mother cry. She and Leonard attended the funeral. She stayed in touch with Coretta, as well as the Abernathys.

“I remember it all,” Ballou says. But much of it she is not telling, to the considerable frustration of her children, who yearn for the stories, to know more of those extraordinary times, but also for their mother to be honored and remembered, to be rendered more than a footnote, for the work she did in assisting civil rights’ greatest champion.

Among the family’s collection from that earlier time, secure in a bank vault, is an autographed $2.95 copy of King’s “Stride Toward Freedom.”

Even if Maude Ballou won’t claim some credit for helping in the early days of the movement, her dear friend and boss chose to do it for her.

In his clean, clear handwriting, King inscribed:

To my secretary Maude Ballou,

In appreciation for your genuine good will, your devotion to your work, and your willingness to sacrifice beyond the call of duty in assisting me to achieve the ideals of freedom and human dignity for our people.

Martin

Clara Jones On WFAE-FM

WFAE-FM Spotlights Clara Jones

It is a special person who can teach music to hundreds of children and quietly turn each of them into success stories. It is with a passion for music and a collection of many pianos that 80-year-old Clara Jones keeps doing just that. WFAE's Victoria Cherrie reports.

Clara Jones is almost ready for work. She’s dressed in a bright orange business suit and sifts through sheet music one more time before students arrive. She bustles through the maze of her old brick house that doubles as her piano studio.

Suddenly, she stops.

She sits at the shiny and black grand piano in the middle of a powder blue living room. Miss Jones then begins to move her long fingers along its ivory keys. She closes her eyes, arching her body to the ebb and flow of the music.

“Music seems to come from the soul, and the more you do it, the longer you do it perhaps the more you feel. Perhaps the more you put yourself into what your doing," Jones says.

Jones has taught piano for 25 years here in her West Charlotte home off Beatties Ford Road. Hundreds of children have touched the keys of her many pianos, much like her teaching has touched them.

“She has a way of giving every single child their individual time and you know making them walk away and feeling like, 'Wow, you know I am somebody special and I can do anything I put my mind to," says Kimberly Jones, who first met Miss Jones as a student 24 years ago.

Few things have changed. The worn Baldwin piano she played when she was 10 is still here in the same pink room with sheet music stacked to the ceiling. Decades later, Miss Jones is still demanding discipline and attention to details from her students.

And she’s still buying pianos. In fact, she has 26. Yes, 26 pianos.

“It’s good to have a number of pianos because when a child may or may not have practiced adequately when you have the pianos there and he can go in to a room by himself and he can practice he learns so much more than if there is just one piano so I love teaching with a lot of pianos.

"(So) of course we had to get 26 of them so that every child who came could stay here until he had mastered whatever he need to master before he left and her certainly left with a better understanding of it,” says Miss Jones.

She says this as three brothers – all working toward scholarships – practice separately in different rooms. Miss Jones has a keen ear and gets up periodically to give instruction.

"If he knows his music, he stays an hour," she says. If he doesn't know his music he stays until Jesus comes."

There are four pianos each in two front rooms where students play side by side. Two more sit back to back in a narrow hallway cluttered with books, boxes and photos of Jones’ four children.

The first piano Jones owned was a Baldwin. But she most fancies a grand.

“A grand piano is different. It has such wonderful sound. It has a big sound, it has a small sound, it has a sound you can hold onto."

She laughs as she recalls buying her first grand piano without telling her husband.

"And the salesperson said, 'Miss Jones, what are you going to tell your husband when you get home?' I said, "I won’t say a word I’ll just bring the piano home, set it up and get him out of the house quickly."

Miss Jones bought so many pianos over the years that her late husband Cedric added on to the house six times. In fact, he didn’t bother removing a set of storm windows he had to build around during one of the last renovations.

The two grand pianos, an organ and two keyboards sit in the blue living room with mirrored walls that is like a center stage. Sliding glass doors lead to the dining room that’s home to two more pianos. The room is converted into a recital hall twice a year.

Jones opened her home studio 25 years ago. Before then, she taught music in CMS for 30 years. But her daughter Ina says she always instilled the importance of music in her own four children.

“On Saturdays, we would have rehearsals and my mother had a station wagon and she would go around picking up the neighborhood children, plus us, and we would all go off to church and practice.”

Kimberly Williams now teaches part time with Miss Jones.

“She always continued to challenge us and wanted to make us play more," Williams says.

But Miss Jones won’t take any credit for and of her students’ successes. Instead, she credits her many pianos. That's why she keeps buying them. She bought yet another a couple months ago.

"I really don't have room for any more, so I guess I don't have to buy any more."